Cocoon review - prepare to be astonished

Bug's life.

Magicians have a concept known as "closing the doors". It's an extremely complex, multi-stage form of lying, basically. You have a good trick, but to make it great, you go around and you spot any avenues of thinking which could lead the audience to work out how it might be done, and then you lock these avenues off, one at a time. It's misdirection, but a sort of nth dimension misdirection.

Cocoon does something similar. Or maybe it's the same thing but through the looking glass, inverted, turned upside down. If magicians close the doors of possibility to stop you from solving a puzzle, Cocoon closes all necessary doors in order to help you solve one. It's closing the doors not in the name of misdirection but, well, direction. And it does it so skilfully I almost always miss those doors closing in the first place.

This is a challenging puzzle game, in other words, but it's never a jerk. And the reason it's never a jerk is all those doors it has closed behind you. If an area's no longer needed, it quietly locks it off. If a puzzle needs you to trek so far for a solution but no further, it will gently place a perimeter around the location. If you need an item, it will find a wordless way to highlight it. Wordlessness! That's a central element here, and we'll come back to it later. For now, what this all means is that when you're stuck, it's always clear where you're stuck, and it's always clear that the solution will be nearby. It will just require some alien logic to find it and implement it. And it turns out that alien logic is pretty easy to uncover when the parameters are so well defined because all those misleading doors have been closed for you.

This is rather a chilly, practical spot to start in on such a game, which I genuinely think is the best game I've played this year. But I'm starting here because I know me, and I know I would hear about Cocoon and think: that sounds brilliant, but it's probably quite a lot of effort? It sounds like an ingenious slog? It sounds, ultimately, like the kind of game I am too stupid for? But with subtle direction implemented throughout the adventure, Cocoon reveals itself as that most holy of all puzzle games - a game so smart that it can make its players feel smart too. I was delighted, frankly.

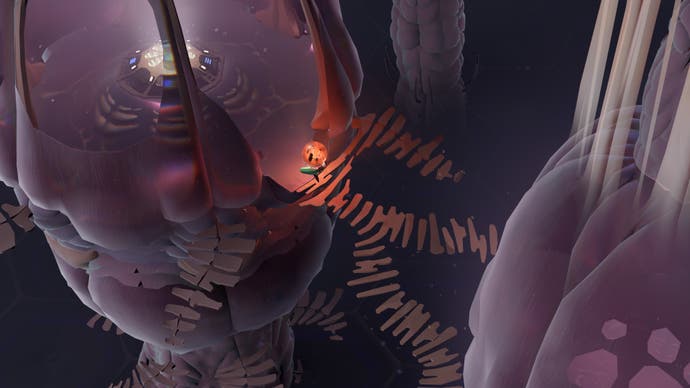

Cocoon is a lot of things nested inside a lot of other things. It's a game about being a little bug wandering about and navigating various obstacles, but you're exploring worlds that are both gloopy and organic, filled with heavily vesseled tumours and sacs and twitching mandibles. Nodes, villi, peristalsis, lymph: Cocoon thrills to the unseen geometry and machinations of life. Amongst other things, it's easily the most bronchial videogame ever made. But it's also strangely futuristic, filled with cabling, junction points, inputs and outputs, copper and bismuth and ceramics.

I think so, at least. In truth, it's hard to know what the game's sprawling, endlessly imaginative bio-technology is made of. A spectrally thin platform riddled with little veins will unfold in front of you and you'll walk on it, your feet letting out a metallic ring. Is this a kind of circuit board, or is it something silken and flexible, like the wings of a fly? When playing I can't work out whether we're wandering amongst stuffed insects or browsing hi-fi components. I guess the truth is that Cocoon has found a point where these two worlds combine. It's ingenious and beautiful and delicately rendered. But it's also swampy and blotted and covered in break-outs. One lunchtime I tried to play Cocoon while eating a sandwich. Bad idea.

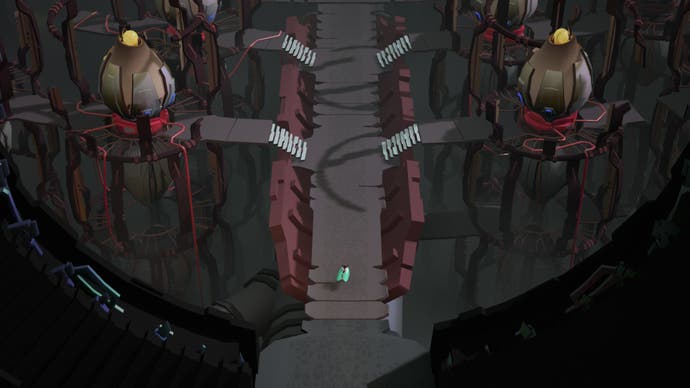

The game itself revolves around a series of spheres you can carry about as you explore a series of these gloopy, glittering worlds. The spheres can be picked up and dropped on certain node points, to bring machinery to life or force life itself to emerge around you. But each sphere also has its own distinct uses. One can raise or lower misty platforms. Another can create brittle, candied pathways beneath you in certain locations. Another can teleport in a way that's so clever I don't want to ruin it. Another can - I had better say no more.

It's funny, but a lot of what these powers are used for amounts to navigating a landscape filled with complicated barriers. It's doors again, but a certain kind of literal door. Often, you'll need to reach a switch that can only be activated by placing a sphere on it, but the path to the sphere is blocked by a fence that you can sneak through - but not if you're holding the sphere! So what do you do? Cocoon has many answers, including pinball tubes you can drop the sphere into, physics toys powered by bouncy platforms, little creatures that can be conjured to affect the environment in certain ways, onwards and outwards, all kinds of fascinating things.

Typically, you'll be in an area where the puzzles will build, Mario style. You'll work out how to do a simple thing, like use a sphere's power, and then the game will lead you to understand how you might turn this power to a new end, invert it, subvert it, discover a fan of new possibilities within it. And it's wordless! Cocoon never ruins the carefully alien mood with overt prompting. It leads the eye, but it never whispers solutions at you. It trusts you! It sees the best in you. It seems to know that you can do things that you would normally suspect that you can't.

All of this is nice, but get this. Each of those spheres you hold and walk around with has one of the game's worlds inside it. And you can access the worlds and move between them by placing the spheres on specific in-game platforms. It's too much, actually. Hold me. Pat my head. Tell me everything will be okay. Cocoon is a game where you can explore a complex world, then roll it up and carry it around. And then deploy it, right, as both a physical container and a contained, independent world, one inside another. You can use the world in the sphere to weight down switches, okay? But maybe there's something you need inside that world to progress in the world that you're currently in. So you can go back inside World A and reappear, moments later, back in World B, with the World A tool that you need to progress in World B, or even World C. You can emerge with useful things in a world that has remained inside another world.

Actually, it goes so much deeper than that. You can nest worlds - for ease of transportation and other things - and carry a couple of worlds inside another, all done up as a sphere you can just heft around. You can move elements through the worlds you have stacked inside other worlds. You can-- but at this point I should let these threads go, for fear of melting everyone's brains including my own. Things happen in this game that I can grasp, but which I cannot afterwards explain.

And yet, as I said before, Cocoon's greatest trick is one of democracy. Written down as above, it sounds like one of those awful books where footnotes stretch across multiple pages and you never quite know when to leap between texts to maintain a thread. But that's my clumsiness, as seen in the fact that I started by talking about doors and now I'm talking about footnotes. Cocoon never tangles itself up like that. Somehow, it takes all these wonderful concepts and delivers them in a way that I can always understand. Not just understand, in fact, but model in my gooey head long enough to actually invent solutions and create possibilities.

Actually, here's another way to think about it. Cocoon is pure delight to play, pure honey on a spoon, but just thinking about how somebody actually made this game - thinking about that even for a second - instantly gives me a migraine. It's the alien logic thing again. This game has an innate understanding of the way humans solve puzzles, but it also seems at times to have come from somewhere else, some other kind of intelligence. A little story here: while I was playing Cocoon one afternoon, a fly, that had been buzzing around the house for a few restless hours, settled on the screen and - I promise you - started to watch. That's what it felt like anyway, and what it really felt like was that the fly had about as much insight into how something like this comes to be as I did. No matter. We were both happy to bask in the wordless astonishment of it all. (Okay, maybe the fly was just resting.)

I could talk for hours about this stuff, and about the density of invention here, both puzzley and visual, about the fact that door animations - doors again - are always complex and fascinating, things folding back, disappearing down inside, slotting together, fanning apart, and how each one feels different, a one-off, even as the game settles into a helpful rhythm paced out in little rituals, most of which defy easy words. I could talk about how each boss is actually a new mechanic to play around with, so I don't dread them, I savour them. These bosses don't kill you, but instead merely chuck you out of the arena so you have to start over. Not good enough, they seem to be saying. Try harder, be more playful, be more thoughtful. Experiment. Look for harmonies.

It's a short game, and quite a painless one, then, but it feels dense: rich and imaginative and the result of some insatiable curiosity for putting things together in new ways. Even at the end of the adventure, five or six hours in, Cocoon was happy to introduce a new mechanic. By which I mean, of course, it was happy to wordlessly teach it, complicate it, turn it inside out and then twist it into something almost unimaginable. I'm sorry to be vague, but you need to see this for yourself. There are no easy words, but also seeing it, witnessing such clarity and ingenuity, is where the pleasure lies.

So much so, in fact, that for one of the game's final puzzles - a puzzle that made me laugh out loud, even though I was alone in the house when I encountered it - I went back after the game was finished, and shaky-cammed the entire sequence using my mobile phone and sent it to a friend. And the message I attached? Jeepers. Look at THIS.

.png?width=240&height=135&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)